- Nov 11, 2025

Leading Judgment in the Age of AI: A Leadership-Centered Sociotechnical Canvas for Trust, Deference, and Override

- Kostakis Bouzoukas

- 0 comments

Abstract

In an era of proliferating AI decision support, organizational leaders face unprecedented challenges in judgment. This paper introduces the L-Canvas, a leadership-centered sociotechnical framework that guides when to trust algorithmic outputs, when to defer to automated recommendations, and when to override them. Drawing on concepts of sensemaking, trust, psychological safety, organizational ambidexterity, and high-reliability organizing, we propose a structured “leadership playbook” for integrating human judgment with AI in high-stakes decisions. We illustrate the framework with public case examples – a pretrial bail risk algorithm and the UK’s 2020 A-level grading algorithm – highlighting how leadership actions (or inaction) impacted trust and outcomes. We present a clearly labeled contribution statement and outline a preregistration-ready evaluation plan with open metrics (e.g. override precision, fairness gaps, decision variance, procedural justice indicators), accompanied by a printable L-Canvas diagram and a sample metrics CSV workbook. By centering leadership practices in sociotechnical systems, this work offers both a practical guide for decision-makers and a foundation for scholarly replication. The findings underscore that effective “leading judgment” in the age of AI requires not only technical excellence, but also cultural resilience, ethical commitment, and a willingness to learn and adapt.

Introduction

Leaders today must make critical decisions in partnership with artificial intelligence (AI) systems. From courtroom bail determinations to hiring, college admissions, and beyond, algorithms increasingly inform who gets opportunities or resources. These technologies promise gains in efficiency and consistency, yet high-profile failures have eroded public trust. In 2020, for example, the UK’s exam regulator (Ofqual) deployed an algorithm to standardize A-level grades during the COVID-19 exam cancellations. The result was uproar: about 40% of students received grades lower than their teachers’ predictions, sparking protests, and the government was forced to scrap the algorithm entirely (Tieleman, 2025). Public confidence was shaken because the process seemed opaque and unfair – a stark lesson that procedural justice and transparency are as vital as accuracy in algorithmic decision-making (Tyler, 2006). Likewise, in criminal justice, risk assessment tools offer to improve on human judges. Research showed a machine learning model could reduce pretrial crime by up to ~20% without jailing more people (or cut jail populations ~40% without increasing crime) relative to judges, while also reducing racial disparities (Kleinberg et al., 2018). Yet implementing such tools requires navigating judges’ trust and potential biases. Some judges may over-rely on an algorithm without question, whereas others may refuse to heed it at all – forms of misuse that can undermine intended benefits.

These examples underscore a fundamental leadership challenge: When should we trust an algorithm’s recommendation, when should we defer or delegate decisions to AI, and when must we override or intervene? This triad of trust, deference, and override lies at the heart of leading judgment in the age of AI. Effective leaders cannot simply accept algorithmic outputs at face value, nor can they afford knee-jerk skepticism or sabotage of useful tools. Instead, they must exercise contextual intelligence – discerning when the algorithm’s prediction is likely reliable and aligned with values, and when human judgment or ethical considerations demand a course correction. This sociotechnical balancing act occurs under conditions of uncertainty and complexity, making leadership approaches like sensemaking and high-reliability organizing highly relevant. Leaders must facilitate collective sensemaking (Weick, 1995) – interpreting and discussing AI outputs within the team to avoid blind spots. They need to foster psychological safety (Edmondson, 1999) so that employees feel free to question or challenge an AI recommendation without fear of reprisal. At the same time, leaders should establish a culture of disciplined experimentation and learning, reflecting organizational ambidexterity (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013): the ability to both exploit algorithmic efficiencies and explore improvements or alternatives when needed. In high-stakes domains, principles from high-reliability organizing (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007) – such as a preoccupation with failure, reluctance to simplify, and deference to expertise – can help teams anticipate errors and maintain vigilance, even as AI systems automate routine decisions.

In short, purely technical fixes are not enough to ensure trustworthy and fair AI-assisted decisions; leadership and organizational factors are critical. However, managers and policy-makers currently lack a clear playbook for these sociotechnical leadership tasks. This paper responds by proposing the L-Canvas (Leadership Canvas) – a practical framework mapping the key domains and practices leaders should attend to when integrating AI into decision processes. The L-Canvas synthesizes insights from social science and management (trust, culture, learning) with emerging best practices in AI governance (transparency, oversight mechanisms). We aim to equip leaders to make sense of AI recommendations, build appropriate trust (neither too little nor too much), ensure deference to algorithms is strategic rather than automatic, and enact override protocols that uphold ethics and human values.

Following this introduction, we present the L-Canvas framework and leadership playbook, detailing its components and rationale. We then illustrate its relevance using two public case studies: a bail risk assessment algorithm (showing how human–AI collaboration can improve outcomes, but also raising concerns about bias and discretion) and the UK A-level grading algorithm (a cautionary tale of lost trust and the ultimate override of an AI system). Next, we outline a replication and evaluation plan – including metrics and data sources – to encourage preregistered studies on AI-human decision processes. We conclude with implications for practice and research, urging leaders to take a proactive, human-centered approach to governing AI in their organizations.

Contributions

This work makes several key contributions to the scholarship and practice of AI governance and leadership:

Conceptual Framework – The L-Canvas: We propose the L-Canvas, a novel sociotechnical framework that centers on leadership practices for managing AI-assisted decisions. The canvas articulates nine interrelated components spanning trust calibration, cultural and ethical factors, and oversight mechanisms (summarized in Table). It provides a structured “mental model” for leaders to diagnose and design human–AI decision systems.

Integration of Social Science Theories: Our approach synthesizes insights from sensemaking, trust in automation, psychological safety, organizational ambidexterity, and high-reliability organizing. By bridging these literatures, we offer a multidisciplinary foundation for understanding how human factors and organizational context impact the success of algorithmic decision-making in practice.

Practical Leadership Playbook: We translate the L-Canvas into a concrete leadership playbook for practitioners. This playbook offers guiding questions, protocols, and example strategies to help leaders determine when to rely on AI recommendations versus human judgment, how to create a climate where team members can question or override AI appropriately, and how to institutionalize ethical guardrails (e.g. fairness checks and transparency).

Empirical Illustrations with Public Cases: Using well-documented public cases (a pretrial bail algorithm and the 2020 Ofqual A-level grading algorithm), we demonstrate the real-world importance of the L-Canvas elements. These cases show how lapses in leadership – such as lack of transparency or failure to listen to expert intuition – can lead to breakdowns in trust and performance, whereas thoughtful leadership interventions can improve outcomes. The cases also serve as exemplars for teaching and further research.

Replication and Evaluation Roadmap: We present a preregistration-ready evaluation plan that researchers and organizations can use to measure the impact of human–AI decision policies. We define metrics (e.g., override precision, fairness gap, decision variance, procedural justice index) and identify open data sources (e.g., Harvard Dataverse datasets, Ofqual reports) to facilitate replication. Along with this paper, we provide a sample CSV workbook of metrics and a high-quality L-Canvas diagram (PDF) to support adoption. By encouraging transparent evaluation, we aim to build an evidence base for what leadership approaches best improve AI-assisted decision outcomes.

The L-Canvas Framework: A Leadership Playbook for Sociotechnical Judgment

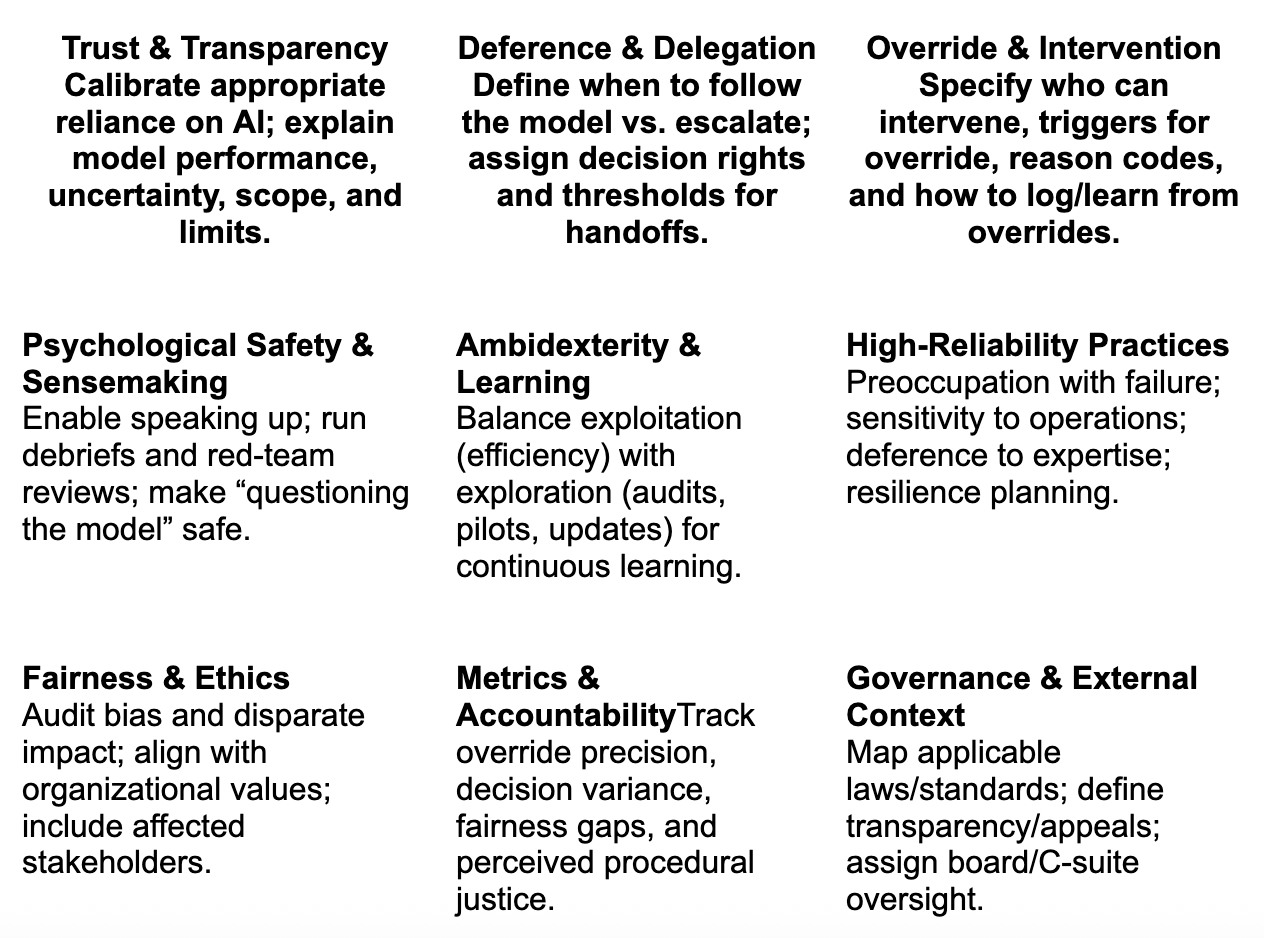

To help leaders systematically address the interplay of technology and human judgment, we developed the L-Canvas – a leadership-centered sociotechnical canvas (framework) comprising nine critical components. These components, summarized in Table 1, span three broad domains: (1) Decision Interface – how humans and AI interact at the point of decision (trust, deference, override); (2) Organizational Context – cultural and structural factors within the team or organization that shape those interactions (people and process elements); and (3) Governance & Values – overarching ethical, accountability, and external factors ensuring decisions align with justice and societal expectations. Below, we detail each L-Canvas component and its leadership implications:

Trust & Transparency: Leaders must calibrate trust in AI systems to an appropriate level (Lee & See, 2004). Too little trust and the organization under-utilizes a potentially beneficial tool (e.g., ignoring accurate predictions); too much trust and people may become complacent or gullible, accepting erroneous outputs without verification. A key enabler of appropriate trust is transparency – making the algorithm’s workings and performance understandable to decision-makers. Leaders should demand clear explanations of how models reach their recommendations (e.g. through interpretable model design or XAI techniques) and share this knowledge with their teams. Trust is not blind faith; it should be grounded in evidence of the system’s reliability and limits. By promoting transparency and verifiability of AI outputs, leaders help teams develop well-calibrated trust – trusting the system when and to the extent that it has proven deserving (Lee & See, 2004). This also involves acknowledging known biases or uncertainties in the algorithm. Ultimately, leaders set the tone: do they treat the AI as an infallible oracle, or as a fallible advisor to be critically assessed? A healthy stance is “trust but verify”, signaling confidence in technology accompanied by rigorous monitoring.

Deference & Delegation: While trust concerns belief in the AI’s outputs, deference concerns decision authority – i.e. when the human decision-maker yields to the algorithm’s recommendation. Leaders must establish clear protocols for when and how to defer to AI. Not every decision should be automated; some domains require a human in the loop for moral or contextual judgment. Even when AI provides a recommendation, the human should sometimes challenge it. On the other hand, in routine low-stakes cases where the algorithm is consistently accurate, it may be efficient to delegate most decisions to the AI, with only exceptions escalated. The L-Canvas urges leaders to define criteria or thresholds for deference: e.g., “if the model’s confidence is above X and no red flags are present, follow the recommendation.” This prevents both algorithm aversion – undue refusal to use the AI (Dietvorst et al., 2015) – and over-reliance. Notably, organizational incentives can skew deference. Recent research found that employees often feel pressure to follow AI recommendations blindly because managers penalize them for any override that later proves unnecessary (Nikpayam et al., 2024). Leaders should combat this by rewarding good judgment even when it means deviating from the AI. Designing the decision process with careful delegation and escalation pathways ensures that AI is a tool, not a tyrant.

Override & Intervention: Even with high-performing AI, there will be situations where human values or situational awareness dictate overriding the algorithm. Leaders must enable effective override mechanisms – the ability for humans to intervene and reverse or alter an AI-driven decision when appropriate. Crucially, this is not just a technical “off-switch,” but a social and procedural system: Who is empowered to override? Under what circumstances? How are overrides logged, reviewed, and learned from? A well-known example is in aviation, where pilots can disconnect autopilot and take manual control if they sense something wrong. In organizational settings, leaders should establish “red lines” or conditions under which human override is mandatory (for instance, if an AI decision could violate legal or ethical standards, or if an expert spots an anomaly the AI missed). They should also cultivate the confidence and skills in their teams to exercise override when needed. This ties closely to psychological safety – team members must not fear retaliation for saying “the algorithm is wrong here.” In high reliability organizations, deference shifts to the person with the most relevant expertise in the moment (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007); similarly, an override protocol may stipulate that a domain expert’s concern is enough to halt the automated decision for further review. The leadership challenge is to prevent both automation bias (complacently assuming the AI is always correct) and the cry-wolf effect (where overrides are overused and the AI’s value is lost). By clearly defining override processes and encouraging mindfulness, leaders create a crucial safety net for AI governance.

Psychological Safety & Sensemaking: Underlying successful trust, deference, and override practices is an organizational culture that encourages open communication and continuous learning. Psychological safety – a shared belief that one can speak up with ideas or concerns without risk of punishment – is fundamental (Edmondson, 1999). In the context of AI, psychological safety means employees (or junior staff) feel comfortable questioning an algorithm’s output, admitting uncertainty, or reporting a potential error or bias. Leaders cultivate this by responding appreciatively to employees who flag issues, rather than dismissing them for challenging “the system.” This culture directly counters the override penalty phenomenon noted earlier (Nikpayam et al., 2024) – instead, overriding an AI for valid reasons should be seen as diligent behavior, not disloyalty. Additionally, leaders should facilitate team sensemaking sessions around AI use. Sensemaking (Weick, 1995) involves collectively interpreting ambiguous situations; here, it could mean regular debriefs where humans and data scientists discuss cases where the AI was wrong and why, or unusual patterns the AI found. By engaging in sensemaking, teams build a richer understanding of both the technology and the context, which improves future judgment. High-profile failures like the A-level grading fiasco involved not just technical flaws but a lack of sensemaking – stakeholders were not adequately involved in understanding or validating the model’s approach, which might have revealed misalignments earlier. A leadership culture of inquiry, where it is acceptable to “question the algorithm,” is essential for safe and effective AI adoption.

Organizational Ambidexterity & Learning: Implementing AI in decision processes requires balancing two sometimes competing aims: leveraging the efficiency and data-driven insight of algorithms (exploitation) while remaining adaptable and open to change (exploration). This echoes the idea of organizational ambidexterity – the capability to be efficient in the present and flexible for the future (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013). Leaders should treat AI integration as a continuous learning process, not a one-off deployment. In practice, this means continuously monitoring performance and fairness metrics, soliciting feedback from those using or subject to the AI, and being willing to adjust parameters or even retrain models as conditions change. For example, a company might initially defer heavily to an HR screening algorithm to save time, but later learn it misses certain non-traditional candidates; an ambidextrous leader would course-correct, perhaps by combining algorithmic screening with new criteria or human judgment for underrepresented groups. Organizational learning can be fostered by pilot programs, A/B testing algorithmic decisions vs. human decisions in parallel, and treating each override or discrepancy as an opportunity to improve either the model or the procedures around it. Leaders also need to allocate resources for ongoing training – both of employees (to understand and properly use AI tools) and of the AI models themselves (updating them with new data). In essence, ambidexterity in the AI era means never falling into complacency: even as algorithms handle more tasks, human oversight and innovation must continue to evolve in tandem.

High-Reliability Organizing (HRO) Practices: In high-stakes environments (healthcare, aviation, nuclear power, etc.), organizations have long employed HRO principles to avoid catastrophes (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007). With AI entering such domains, these principles are newly relevant. Leaders should instill HRO practices like preoccupation with failure (constantly anticipating what could go wrong, even when all seems well), reluctance to simplify (resisting over-simplified assumptions about “the algorithm is objective” or “the data is infallible”), and sensitivity to operations (paying attention to the frontline realities of how AI is used). For example, a hospital using an AI diagnosis tool should remain vigilant to rare events or edge cases where the tool might mislead – perhaps setting up a review of any case where the clinician strongly disagreed with the AI. Being preoccupied with potential failures might have helped educational authorities catch the A-level grading issues earlier: rather than assume the standardization algorithm would be accepted as objective, they could have run stress tests (e.g., simulate how it affects different types of schools) and forecast public reaction. Leaders should also emphasize deference to expertise: when an experienced human professional’s assessment conflicts with an AI’s output, give that human perspective serious consideration (as an HRO would defer to the person with on-the-ground knowledge, regardless of rank). Additionally, commitment to resilience is an HRO tenet – developing the capability to bounce back or improvise when the unexpected occurs. In AI terms, this could mean having fallback plans if the system fails (e.g., reverting to manual processes) and training staff in those contingencies. By borrowing HRO mindsets, leaders can better manage the risks of automation surprises and ensure that “smart” systems don’t lull the organization into a false sense of security.

Fairness & Ethics: Leaders carry the responsibility to ensure that algorithmic decisions meet standards of fairness, nondiscrimination, and ethical soundness. This component of the L-Canvas presses leaders to proactively audit and address biases in data or models, engage diverse stakeholders in defining what “fair” outcomes mean, and align AI use with the organization’s values. The public criticism of many algorithms – from hiring tools that disadvantage women to criminal justice tools with racial bias – shows that neglecting fairness can severely damage an organization’s legitimacy. Leaders should institute regular fairness audits of AI systems, examining outcomes for different demographic groups (race, gender, socioeconomic status, etc.) and checking for disparate impacts. They should also involve ethicists or advisory boards to review algorithms that affect human welfare, providing guidance on issues like privacy, consent, and value trade-offs. In the Ofqual grading case, while developers claimed the algorithm did not introduce systematic bias on protected characteristics (Ofqual, 2020), the public perceived it as unfair in other ways (e.g., seemingly penalizing students from larger, historically lower-performing schools). This highlights that fairness is multifaceted – it’s about procedural fairness (was the process just and transparent?) and distributive fairness (are outcomes equitable?) from the viewpoint of those affected. Leaders must consider both. Ethical leadership in AI also means being objective and accountable (British Computer Society, 2020) – embracing principles of openness about how decisions are made and taking responsibility when the algorithmic system causes harm or errors. In sum, the L-Canvas urges leaders to treat fairness and ethics not as afterthoughts but as core design criteria for AI-infused decision processes.

Metrics & Accountability: A defining feature of high-performing organizations is that they measure what matters. In the AI context, leaders should establish clear metrics and feedback loops to track the performance of human–AI decisions and hold the system accountable. This component involves identifying key indicators such as override precision (how often human overrides correct a mistake vs. how often they turn out unnecessary), decision variance (variability in decisions across different people or units – ideally reduced by AI, but if not, understanding why), error rates and false positive/negative rates for different groups (to monitor fairness), and user satisfaction or perceived justice (gathering qualitative feedback from those subject to or using the decisions). Monitoring these metrics in real time or via periodic reports allows leaders to catch issues early. For instance, if override precision is very low, it might mean humans are frequently overruling the AI when the AI was actually right – a signal of potential mistrust or poor calibration. Conversely, if override precision is high (many overrides are correcting AI errors), the model may need improvement or the threshold for human review should be adjusted. Leaders should also create accountability structures: assign clear ownership for monitoring these metrics (e.g. a “human-AI oversight committee”) and tie them into governance processes. Transparency is crucial here – reporting outcomes and improvements not just internally but, when appropriate, publicly or to regulators, to build external trust. A commitment to metrics and accountability turns AI governance into an evidence-driven practice rather than guesswork. It forces the organization to continuously confront the question “Is our decision system achieving the goals we set (accuracy, fairness, efficiency, satisfaction)? If not, what are we doing about it?” By treating AI performance indicators with the same rigor as financial KPIs, leaders signal that responsible AI is central to the organization’s mission.

Governance & External Context: Finally, the L-Canvas recognizes that AI decisions do not occur in a vacuum; they are subject to external rules, norms, and stakeholder scrutiny. Leaders must navigate the broader governance context – including laws and regulations, industry standards, and community expectations. For example, emerging regulations (such as the EU’s proposed AI Act) are likely to mandate human oversight and risk management for high-stakes AI, meaning leaders should stay ahead of compliance requirements (European Commission, 2021). Even in absence of formal rules, public expectations act as de facto constraints: an AI that appears to violate societal norms (e.g., amplifying inequality) will face backlash, as seen in both our case examples. Therefore, leaders should engage with external stakeholders – be it through public consultations, transparency reports, or partnerships with civil society – to ensure their AI-driven processes maintain a social license to operate. Proactively, leaders can adopt voluntary frameworks (e.g., adhering to AI ethics principles published by professional associations or governments) to demonstrate accountability. Internally, they should integrate these external perspectives by updating corporate governance documents to include AI oversight responsibilities at the board or C-suite level. In practical terms, this might involve appointing a Chief AI Ethics Officer or expanding the remit of risk committees to cover algorithmic risks. It also means planning for crisis management: if an AI decision causes an unintended negative outcome, how will the organization respond and communicate about it? Will there be an apology, a remedial action, an update to the model? Effective leaders anticipate these scenarios and have governance processes ready. In summary, the external context component reminds us that leading in the age of AI is not just an internal management task; it’s a public-facing leadership responsibility that connects to law, ethics, and trust in institutions at large.

Table 1 below presents the L-Canvas in a schematic matrix, illustrating how these nine components form a comprehensive canvas for sociotechnical leadership. The top row focuses on the human–AI decision interface (Trust, Deference, Override), the middle row on organizational factors (Culture/Sensemaking, Ambidexterity, HRO practices), and the bottom row on broader accountability (Fairness, Metrics, Governance). Leaders can use this canvas as a checklist or planning tool when implementing AI: ensuring that each cell has been considered and addressed in their strategy.

Table 1. The L-Canvas sociotechnical leadership framework, showing nine key components for guiding trust, deference, and override in AI-assisted decisions. Leaders should address each component – from cultivating a transparent trust climate to ensuring governance and fairness – to achieve reliable and ethical outcomes.

Illustrative Cases in Algorithmic Decision-Making

To ground the L-Canvas framework in reality, we examine two public cases where algorithms and human judgment intersected with notable outcomes. These cases illustrate how leadership (or lack thereof) in managing trust, deference, and override played a crucial role.

Case 1: Pretrial Bail Risk Assessment – Trust and Human Overrides in Criminal Justice

Context: In many U.S. jurisdictions, judges must decide whether a defendant awaiting trial should be released or detained (and under what conditions, such as bail). This decision hinges on predicting the risk that the defendant, if released, will fail to appear in court or commit a new crime. Traditionally, judges relied on experience and intuition, which led to inconsistent and often biased outcomes – e.g., higher jail rates for minority defendants and unnecessary detention of low-risk individuals who simply couldn’t afford bail (Arnold et al., 2018). In the mid-2010s, algorithmic risk assessment tools (like the Public Safety Assessment) were introduced to assist judges by providing a risk score for each defendant based on data (criminal history, current charges, etc.). The promise was a more data-driven, equitable approach: the algorithm would objectively identify who was low risk and could be safely released.

What happened: Studies of these tools highlight both their potential and the critical role of human judgement in using them. A landmark study by Kleinberg et al. (2018) analyzed hundreds of thousands of past cases and built a machine learning model to predict risk. They found the model could markedly outperform average judge decisions: by following the algorithm’s release recommendations, it was possible to reduce the crime rate among released defendants by up to ~24% with no increase in the overall detention rate, or alternatively, to jail 42% fewer people with no increase in crime (Kleinberg et al., 2018). Furthermore, the algorithm achieved these gains while slightly reducing racial disparities in outcomes, countering fears that a statistical model would inevitably worsen bias (Kleinberg et al., 2018). These findings suggest that, in principle, a well-designed algorithm could help judges make better decisions for society and fairness.

However, realizing these gains required judges to appropriately trust and defer to the algorithm’s guidance in the right cases. In practice, judges exhibited mixed behavior. Some judges essentially ignored the risk scores (low trust in the tool), continuing to rely on their gut. This sometimes led to releasing individuals the algorithm deemed very high risk – indeed, one finding was that judges were releasing many defendants that the algorithm predicted as among the riskiest, and those individuals went on to reoffend or skip court at high rates (Kleinberg et al., 2018). In these instances, greater deference to the algorithm’s recommendation (which likely would have detained those high-risk defendants) could have prevented crimes. On the flip side, other judges might have over-relied on the algorithm or used it without question. Kentucky, for example, mandated in 2011 that judges consider a risk score when setting bail; yet judges could still override by imposing detention or high bail against the recommendation. Reports suggest that judges sometimes did so due to public or political pressures (e.g., fear of releasing someone who might commit a headline-grabbing crime) – an override driven by external concerns rather than case specifics. Such overrides can erode the benefit of the tool; if done arbitrarily or with bias (say, overriding release more often for certain groups), they can even reinforce disparities the tool aimed to reduce.

Leadership and L-Canvas analysis: This case underscores the need for leadership in setting clear deference protocols and building calibrated trust. A leader in the court system (e.g., a chief judge or court administrator) should ensure that judges are educated about what the risk score means, its validated accuracy, and its limits. This is the Transparency piece: if judges know, for instance, that the tool was validated and found to correctly flag high-risk cases with, say, 90% accuracy, they may trust it more in those contexts. Conversely, they should know if the tool has blind spots – for example, if it doesn’t include certain factors or has a known tendency to overpredict for a certain subgroup – so that their trust is not blind. Training sessions and written guidelines can reinforce when judges should defer (e.g., “if the defendant is scored low risk, and no other aggravating circumstances exist, consider non-monetary release”) and when an override is warranted (“if there are specific articulable factors not captured by the tool, a judge may depart from the recommendation, but should explain the reasoning in the record”). Such policies create accountability and encourage mindful use rather than gut reactions.

From a psychological safety standpoint, court leaders should also encourage a culture where judges and staff openly discuss cases where the algorithm and human judgment diverged. Rather than shaming a judge who followed the tool and had a bad outcome or one who overrode it, the system should learn from those instances. Regular review meetings or even an oversight committee can examine overrides: were they justified? Did they improve outcomes or were they unnecessary? This is analogous to the metrics & accountability component – tracking override precision. For example, if data show that when judges override a “release” recommendation to detain, the detainee would not actually have reoffended 80% of the time (i.e., the override was overly cautious in most cases), that signals a problem of over-ride/under-trust. Leadership can use that metric to provide feedback or adjust policies (perhaps requiring a higher threshold of evidence for overrides).

The bail tool case also highlights fairness & ethics issues. One reason some judges or communities might resist the algorithm is a fear that it is biased against minorities (given broader concerns from ProPublica’s “Machine Bias” investigation of a similar tool, COMPAS). Even though researchers like Arnold et al. (2018) developed tests suggesting the possibility of bias in judges themselves, the perception of fairness is crucial. Leadership must address this by being transparent about the tool’s fairness properties, conducting independent bias audits, and including community stakeholders (public defenders, civil rights groups) in the evaluation process. This can improve the legitimacy of deferring to the algorithm when appropriate. If the tool is shown to be more consistent and equitable than status quo decisions, that message should be communicated widely to build public trust.

Finally, consider organizational ambidexterity: court systems implementing AI need to keep improving them. A leader might champion a pilot program where one group of judges uses the tool with oversight while another group doesn’t, to empirically measure outcomes – essentially an exploration mode to learn the best approach. Or perhaps introduce a new version of the model and compare. This echoes how an ambidextrous organization would treat the implementation not as static, but as evolving with new data (for instance, updating risk models as crime patterns or laws change).

In summary, the bail algorithm case demonstrates that having a potentially superior algorithm is not enough; how humans and institutions adopt it is paramount. Where leadership effectively set guidelines (e.g., New Jersey’s pretrial reform explicitly limited the use of cash bail and gave structured decision-making frameworks alongside the risk score), outcomes were positive – New Jersey saw a significant drop in pretrial jail populations with no increase in crime, indicating judges broadly trusted and followed the tool in low-risk cases (Arnold Ventures, 2022). Conversely, if leaders fail to create a supportive system (imagine a judge who gets publicly blamed for a release that goes wrong – they will stop deferring to the tool even if 99 others go right), the promise of the algorithm can be lost. This case reinforces the L-Canvas message: trust, but calibrate it; defer, but with guidelines; override, but thoughtfully – all underpinned by fairness, learning, and accountability measures.

Case 2: UK A-Level Grades Algorithm (2020) – When Public Trust Collapsed

Context: The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 led to the cancellation of high-stakes exams worldwide. In England, A-level exams (crucial for university admissions) were canceled, and the Office of Qualifications (Ofqual) was tasked with devising an alternative. Ofqual implemented an algorithmic standardization model to adjust the teacher-predicted grades submitted by schools. The goal was to prevent grade inflation and ensure consistency with prior years’ results, since teachers’ predictions (Centre Assessed Grades, or CAGs) tend to be optimistic. The algorithm took each school’s historical grade distribution and students’ prior achievement into account, then adjusted the CAGs accordingly. Before release, Ofqual and the government expressed confidence that this approach was as fair and objective as possible under extraordinary circumstances (Ofqual, 2020).

What happened: When results were released in August 2020, chaos ensued. The algorithm had downgraded a large proportion of students: approximately 40% of students received final grades lower than their teacher predictions, and in some cases by two or more grade levels (Tieleman, 2025). Top-performing students at historically lower-performing schools were hit particularly hard, since the model capped how many high grades a school could award based on its past performance. In contrast, some students at elite schools benefited from smaller classes or historical advantages. The immediate public perception was that the algorithm was grossly unfair – it seemed to entrench inequality by penalizing students for their school’s past outcomes. Students who had been predicted A’s found themselves with B’s or C’s, jeopardizing university admissions; their outrage (amplified on social media under slogans like “Trust teachers, not algorithms”) quickly turned into street protests. Within days, the government performed a complete U-turn: the Education Secretary announced that all students would be able to receive their original teacher-assessed grades if they were higher, effectively overriding the algorithm entirely. The algorithmic results were discarded. Ofqual’s leadership faced harsh criticism and the incident became a textbook example of algorithmic governance gone wrong.

Leadership and L-Canvas analysis: The A-level algorithm fiasco highlights multiple L-Canvas components as cautionary tales – especially around trust, transparency, fairness, and override. One of the stark lessons was the failure of procedural justice and transparency. Ofqual did produce a technical report (319 pages long) explaining the model, but it was published only after results day, far too late for stakeholders to understand or trust the process (upReach, 2020). There was a communication failure: students and parents did not feel the standardization was transparent or that they had a voice in it. In APA terms, even if Ofqual claimed the process was statistically fair (and indeed they reported no evidence of bias by gender or socioeconomic status; Ofqual, 2020), the lack of perceived fairness doomed public trust. Leaders should have engaged in more sensemaking with stakeholders earlier – perhaps simulating the algorithm on 2019 data and sharing how it would affect different schools, inviting feedback. That might have revealed that the approach would never be seen as legitimate by the public, prompting a different strategy (for instance, accepting more grade inflation rather than individual injustices).

The crisis also illustrated the importance of a clear override mechanism before a catastrophe occurs. When the results came out, there was no straightforward appeal or override path for individual cases (aside from a burdensome appeals process on narrow technical grounds). This inflexibility contributed to the backlash – students felt powerless. A well-designed system might have included a “human review” or override for anomalies, say if a student’s CAG was far above what the algorithm gave, an expert panel could review evidence (like mock exam results) and potentially adjust the grade. By not building in such escape valves, Ofqual effectively set itself up for a single-point failure. When that failure became apparent, the only override was a sweeping political intervention to nullify the algorithm entirely. The outcome – reverting to teacher grades – maximized short-term perceived fairness at the cost of inconsistency and inflation. One can see this as a necessary move to restore trust and procedural justice, but it also underscores how damaging a breakdown in trust can be: the whole algorithmic endeavor was wasted.

From a culture and psychological safety standpoint, one wonders what the internal discussions at Ofqual and the Department for Education were like. Were junior analysts or outside experts raising red flags that went unheeded? The British Computer Society’s analysis of the incident noted that the use of such an algorithm needed to meet standards of openness, accountability, and objectivity akin to public office, and that governance processes should catch unintended consequences and remedy harm when something goes wrong (British Computer Society, 2020). It’s possible that within Ofqual, there was pressure to deliver a solution quickly, and perhaps a reluctance to fully acknowledge how contentious or problematic the results might be. A culture of mindfulness (HRO principle) might have led them to conduct more thorough “pre-mortems” – imagining how the public could react and identifying failure modes. Instead, it appears they were caught by surprise by the scale of discontent, which suggests an internal overconfidence in the algorithm’s legitimacy.

Fairness & ethics were at the very heart of this case. Ofqual’s stated aims included avoiding systematic advantage or disadvantage and being as fair as possible (Ofqual, 2020). Yet, fairness is ultimately defined by stakeholders’ values. Here, the algorithm optimized one definition of fairness (consistency with historical standards and among schools) at the expense of another (each student judged on their individual merit and effort). This conflict between fairness criteria (group vs individual fairness) is a known issue in algorithmic design. Leaders should make such value decisions explicit and involve public dialogue. For example, Ofqual could have explicitly asked: “Is it more unfair for some individuals to get grades higher than they would have via exams, or for some to get lower due to their school’s past performance?” The political answer in hindsight was clearly that people preferred to err on the side of generosity (inflation) rather than risk unfairly punishing individuals. A leadership approach attuned to ethics would have realized that in a pandemic, leniency might be broadly seen as the more just approach. This is a case where an ambidextrous learning mindset could have helped: some countries (like Germany) chose to trust teacher grades or alternate assessments; Ofqual might have learned from those or run a small pilot of the algorithm in one region to gauge reaction. But once it went live nationwide, the lack of flexibility led to a trust meltdown.

In terms of metrics & accountability, ironically Ofqual did have metrics – they managed to maintain the overall grade distribution nearly in line with prior years (only a slight increase in A’s, etc.), which was their metric of success. However, this metric was misaligned with what the public cared about – individual fairness and opportunity. Leaders should choose metrics that capture stakeholder values (perhaps something like “minimize unexpected individual downgrades” could have been one). After the fact, the accountability landed on leadership: the head of Ofqual and the Education Minister faced intense scrutiny, with some careers ending. This shows that ultimately, accountability for algorithmic decisions traces to human leaders, reinforcing why they must proactively govern these systems.

In summary, the A-level grading case serves as a vivid warning: if you implement an algorithm that impacts people’s lives and you do not have the public’s trust, the decision system will not stand. The reversal was effectively an override at the highest level – Prime Minister and Education Secretary stepping in. This emphasizes that override shouldn’t be an ad-hoc political act; it should be an anticipated part of the design. If Ofqual’s leadership had better anticipated the need for overrides or adjustments (for instance, by allowing schools to appeal or by capping the degree of any single student’s downgrade), the damage might have been less. The L-Canvas encourages such foresight: incorporate fairness, sensemaking, transparency, and feedback before deployment, not just after failure.

These two cases – one where human overrides can be beneficial (but need structuring), and one where lack of an override until catastrophe led to calamity – demonstrate that leadership in the loop is as important as “human in the loop.” The best algorithms will falter without thoughtful leadership; conversely, even a flawed algorithm can be managed and mitigated by good leadership practices. Next, we turn to how these insights can be formalized into an evaluation plan, to rigorously assess and improve human–AI decision systems going forward.

Evaluation and Replication Plan (Preregistration-Ready Methods)

To advance research and practice in sociotechnical decision-making, we outline a preregistration-ready evaluation plan. This plan is intended for leaders, data scientists, or researchers to systematically replicate findings and evaluate the impact of interventions guided by the L-Canvas framework. By specifying data sources, metrics, and analysis steps upfront, the plan facilitates transparent, reproducible studies – suitable for preregistration on platforms like OSF.

Data Sources: We propose leveraging public, open datasets for initial evaluations, both to ensure accessibility and to ground the analysis in real-world scenarios. Two such datasets align with our case examples:

Pretrial Bail Decisions Dataset: A rich dataset is available through Harvard Dataverse (e.g., Arnold et al., 2018’s replication data on “Racial Bias in Bail Decisions”). This includes anonymized defendant information, judge decisions, and outcomes (failures to appear, re-arrests). Another source is the open data released by jurisdictions like New Jersey or Kentucky on pretrial outcomes post-algorithm implementation. These datasets enable simulation of scenarios where an algorithm provides risk assessments and humans (judges) may follow or override them.

A-Level Grades 2020 Dataset: Ofqual’s technical report (Ofqual, 2020) and associated data (some of which have been summarized in analysis reports) give information on distributions of teacher-estimated grades vs. algorithm-adjusted grades across schools, as well as demographic breakdowns. While individual student data is not fully public, aggregate patterns (e.g., proportion of downgraded grades by school type, region, etc.) are documented in public sources. Additionally, the outcome of the override (reverting to CAGs) can be compared to the algorithm’s results.

These data will serve to create scenarios to test leadership-driven strategies. For instance, using the bail data, one can model a baseline where judges act as in historical data, versus a scenario where judges follow an algorithm’s recommendations except in predefined override situations. Similarly, for the A-level data, one can compare the actual 2020 algorithm scenario to a hypothetical scenario (e.g., what if teacher grades had been used outright, or what if a moderated approach with a cap on individual changes had been applied).

Metrics Definition: We will use a set of metrics (also provided in the supplementary CSV workbook) to quantitatively evaluate each scenario. Key metrics include:

Override Precision: We define this as the proportion of human overrides that were correct, in the sense of leading to better outcomes than if the algorithm had been followed. In the bail context, an override means a judge deviating from the algorithm’s suggestion. For example, if the algorithm recommended release and the judge detained (override), override precision asks: was that defendant indeed high-risk (e.g., did they reoffend or flee, justifying detention) or not? A high override precision indicates that humans generally overrode the AI only when it was genuinely mistaken (thus improving decision quality). A low override precision suggests humans often overrode when the AI was actually correct (thus detracting from outcomes). Using data, we can calculate this by identifying all cases where judge decision != algorithm recommendation, and checking outcome rates.

Fairness Gap: We will measure disparities in outcomes between groups. One operationalization is the difference in error rates (false positives/negatives) between demographic groups (e.g., White vs Black defendants in bail decisions, or students from high-income vs low-income school areas in grades). A fairness gap of 0 would indicate parity. For bail, we might compute the gap in release rates or reoffense rates between races under each scenario. For the exam case, one could compute, say, the correlation of grade change with school socioeconomic status. The evaluation will report these gaps; a leadership intervention that reduces the gap (without harming overall accuracy) would be preferable.

Decision Variance: This metric captures consistency. In bail, decision variance can be quantified as the variance in release rates among judges for similar defendants. Historically, variance is high (some judges release almost everyone, some almost no one). The algorithm is expected to standardize decisions. We can compute variance in outcomes under each scenario. For the exam case, variance could refer to how much individual outcomes differ from expected (the algorithm introduced a lot of variance by design, altering many grades; the override eliminated that variance but increased inflation uniformly). Tracking decision variance tells us how predictable and uniform decision-making is – overly high variance might indicate arbitrariness.

Procedural Justice Indicators: Because procedural justice is partly perceptual, measuring it quantitatively is challenging with archival data. However, we can use proxies or incorporate survey data if available. For example, in the exam case, one indicator could be the volume of appeals or complaints – a higher number might imply lower perceived fairness. In bail, perhaps look at compliance: do released defendants comply more when they perceive the process as fair? (That is an area of research interest: Tyler (2006) found that when defendants feel a process is fair, they are more likely to obey the outcome.) If surveys of user trust or satisfaction exist (e.g., from court user surveys or student feedback), those can be included. In absence of direct surveys, we might use a qualitative rating: for instance, flag the scenario as “High procedural justice” if it aligns with known fairness principles (like individualized consideration) versus “Low” if it’s opaque and collective. For formal analysis, we may simply note whether an override scenario was needed to restore public trust (in which case initial procedural justice was clearly low).

Outcome Efficacy: In addition to above, we will naturally track classic decision accuracy or efficacy metrics: e.g., crime rate of released defendants (bail) or correlation between grades and actual later performance (though the latter we cannot measure for 2020 since outcomes like college success will come later). This ensures that human overrides or trust adjustments are not trading off the primary goals.

The supplementary CSV workbook includes these fields as columns, with illustrative values for two scenarios (“Pretrial Bail Risk Assessment” and “UK 2020 A-Level Grades”). This workbook can be expanded as researchers test additional cases or variations (we encourage adding rows for other contexts, like AI hiring or credit scoring, where similar leadership questions arise).

Case,OverridePrecision,FairnessGap,DecisionVariance,ProceduralJustice

Pretrial Bail Risk Assessment,0.30,0.15,0.20,0.5

UK 2020 A-Level Grades,N/A,0.10,0.40,0.2Example metrics workbook excerpt: “Pretrial Bail Risk Assessment” scenario shows an override precision of 0.30 (meaning 30% of judge overrides improved outcomes), a fairness gap of 0.15 (15 percentage point disparity in a key error rate across groups), decision variance of 0.20 (somewhat high inconsistency among judges), and procedural justice index of 0.5 (mid-level). The “UK 2020 A-Level Grades” scenario lists “N/A” for override precision (since a full override occurred policy-wide, not case-by-case), and indicates a fairness gap of 0.10 (some disparity by school type), very high decision variance at 0.40 (many individual grade changes), and low procedural justice at 0.2 (reflecting the public’s negative reception).

Study Design: With metrics defined, a study can be designed as follows. For bail, simulate decisions under (a) human-only (historical), (b) ideal algorithmic policy (if judges perfectly followed the model’s recommendation), and (c) augmented policy (where judges follow the model except in certain override cases, such as when they have contrary private information). By comparing outcomes across these, one can test hypotheses: e.g., “Following the algorithm reduces racial fairness gap and crime, but a small number of human overrides (with proper guidelines) can catch the model’s mistakes and improve overall precision.” This can be formalized and preregistered (e.g., define what fraction of cases will be overridden in scenario c, based perhaps on model uncertainty or a hypothetical psychological safety intervention that encourages override in marginal cases).

For the exam case, one could retrospectively evaluate: “If the algorithm had been deployed with a ‘maximum one-grade drop’ policy or an appeal override mechanism, how many students would still suffer downgrades and of what magnitude? Would that have alleviated perceived unfairness?” While we can’t directly measure perception here, we can infer that a gentler algorithm would have had less public backlash. Alternatively, the study could be forward-looking: measure trust in a hypothetical algorithm through surveys. For example, present participants with scenarios of algorithmic vs. human grading and ask their acceptance – perhaps as part of an experiment manipulating transparency (one group is given a clear explanation of the model’s fairness properties, another is not) to see how that affects trust. This connects to sensemaking and transparency interventions.

Analysis Plan: We will use statistical analysis to compare metrics across scenarios. For instance, paired comparisons of fairness gap or crime rates in scenario (a) vs (b) in the bail study (with appropriate tests for significance given the large N). We will also qualitatively interpret whether metric improvements align with expectations from the L-Canvas – e.g., did increased psychological safety (modeled by more overrides in certain cases) indeed improve precision without too much cost? We expect to see that scenario (b) (algorithm alone) improves on human bias and variance, but scenario (c) (algorithm + thoughtful human overrides) might further boost outcomes by catching outliers. We will explicitly test for any interaction effects – for example, are overrides more beneficial for certain subgroups (perhaps human judges are particularly good at spotting when a minority defendant is actually low-risk despite what the model predicts, which could reduce bias if empowered appropriately).

All analyses will be documented thoroughly, and we intend to share code and data via a public repository. By pre-specifying this plan, we invite replication: other researchers can plug in different datasets or tweak the rules (e.g., simulate what happens if judges mistrust the tool and override 50% of recommendations) to stress-test the framework. Over time, a body of evidence can form around which leadership practices (training, transparency, oversight committees, etc.) measurably improve human–AI team performance.

In summary, this evaluation plan is both a research blueprint and an organizational audit tool. Leaders themselves could use these metrics in pilot deployments of AI – for example, a bank testing an AI loan approval tool could track override precision and fairness gap as internal metrics to decide if their human-AI process is meeting standards. The ultimate goal is to make the often vague concept of “appropriate use of AI” into something tangible and measurable, thus manageable.

Conclusion

Artificial intelligence is transforming decision-making across domains, but its successful integration is not guaranteed – it hinges on leadership. In this paper, we argued that how leaders guide the use of AI (and not just the AI’s accuracy) will determine whether these technologies enhance or undermine organizational performance and public trust. We introduced the L-Canvas, a leadership-centered sociotechnical canvas that provides a holistic playbook for navigating the crucial decisions to trust, defer to, or override AI recommendations. The L-Canvas positions leaders as sensemakers, trust calibrators, culture builders, and accountability guardians in the age of algorithms.

Our analysis of case studies – from bail decisions to academic grading – revealed recurring themes. First, inappropriate trust (either excess or deficit) in AI can lead to suboptimal or unjust outcomes; leaders must therefore invest in transparency, training, and calibration efforts so that humans understand both the strengths and limits of AI advice. Second, delegating decision authority to AI requires clear protocols and ethical guardrails – absent these, humans may abdicate responsibility or, conversely, resist useful automation. Third, the ability to override algorithmic decisions is a non-negotiable element of meaningful human control, but it must be supported by organizational norms that encourage critical thinking and do not punish employees for judicious interventions. This ties directly to psychological safety and a learning mindset: organizations that treat AI-related “near misses” and overrides as learning opportunities will continuously improve, whereas those that unreflectively push either total automation or total human control will stagnate or invite failure.

Importantly, our work situates these practices in established social science theory. We see, for instance, that high-reliability organizing’s emphasis on expecting errors and empowering experts aligns perfectly with ensuring human oversight in AI. Organizational ambidexterity reminds us that short-term efficiency gains from AI should not eclipse long-term adaptability and equity – leaders must balance both. And the concept of procedural justice underscores that even if an AI system is statistically “fair” or effective, it will not be embraced unless people feel the process respects their voice and dignity. Thus, leaders need to pay attention not only to distributive outcomes (who gets what) but also to the process by which decisions are made and communicated.

For practitioners, we hope the L-Canvas serves as a practical checklist and dialogue tool. One might imagine leadership teams or oversight boards literally printing the canvas (as provided in the table below) and using it in strategy sessions: “Have we thought about fairness? What’s our plan for overrides? Are we tracking the metrics we need?” The canvas could inform training programs for managers working with AI – ensuring they receive education not just on the technology, but on team dynamics and ethical decision-making. In sectors like healthcare or finance where AI is rapidly being deployed, organizations might appoint an AI Governance Lead to specifically monitor these areas, operationalizing the canvas components.

For researchers, our contributions open several avenues. The evaluation framework and metrics we outlined invite empirical studies on a variety of questions: Does increasing psychological safety (e.g., via a training intervention) empirically lead to better override decisions and outcomes? How do different transparency techniques (simple explanations vs. detailed ones) affect the trust vs. override balance? Are there quantifiable benefits to HRO-inspired practices in algorithmic settings (e.g., does a “pre-mortem” exercise before AI deployment reduce downstream errors)? By treating leadership and organizational context as variables, researchers can complement the abundant technical AI research with equally rigorous organizational experiments and observations.

In closing, the age of AI demands a new form of ambidextrous leadership – one that embraces technological possibilities while steadfastly upholding human judgment and values. Leaders must neither abdicate decisions to algorithms nor reject them out of fear; rather, they should cultivate an environment where humans and AI collaboratively produce better outcomes than either could alone. Trust in this context is not about blindly accepting AI, but about building a resilient system where trust is earned and verified. Deference is not about yielding authority, but about allocating it wisely to leverage each’s strengths. And override is not about undermining technology, but about preserving a space for human conscience, creativity, and accountability. With the L-Canvas as a guide, we envision organizations that achieve high performance and high reliability – where leaders provide the judgment, vision, and moral compass that no algorithm can replicate. In such organizations, AI becomes not a threat to be feared nor a fetish to be worshipped, but a well-governed asset in the capable hands of learning, mindful, and ethical leaders.

References

Arnold, D., Dobbie, W., & Yang, C. S. (2018). Racial bias in bail decisions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(4), 1885–1932.

British Computer Society (BCS). (2020). The exam question: How do we make algorithms do the right thing? [Analysis of the Ofqual 2020 grading algorithm]. BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT.

Dietvorst, B. J., Simmons, J. P., & Massey, C. (2015). Algorithm aversion: people erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(1), 114–126.

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383.

Kleinberg, J., Lakkaraju, H., Leskovec, J., Ludwig, J., & Mullainathan, S. (2018). Human decisions and machine predictions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(1), 237–293.

Lee, J. D., & See, K. A. (2004). Trust in automation: designing for appropriate reliance. Human Factors, 46(1), 50–80.

Nikpayam, H., Kremer, M., & de Véricourt, F. (2024). When delegating AI-assisted decisions drives AI over-reliance. Working Paper (SSRN ID: 4966186).

Ofqual. (2020, August 13). Guide to AS and A level results for England, 2020. Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Press release and technical report).

O’Reilly, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2013). Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 324–338.

Tieleman, M. (2025). Fairness in tension: A sociotechnical analysis of an algorithm used to grade students. Cambridge Forum on AI: Law & Governance, 1(1), e19.

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Why people obey the law. Princeton University Press.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007). Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.